A Quick Film Review

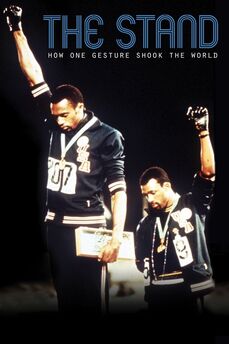

The recent reiteration by the International Olympic Committee of its controversial Rule 50 - in effect prohibiting podium protests - inspired a look at last year's The Stand: How One Gesture Shook the World, a retrospective documentary on the famous original Olympic protest.

Ahead of the Games, civil rights activism in the U.S. was at a fever pitch. Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination had occurred, and a new generation of Black and allied citizens were inspired to have their voices heard against injustice. In The Stand, select perspectives of discrimination from U.S. athletes are presented, including track & field teammates Ralph Boston, Mel Prender, and Patty von Wolvelaere. Packaged with the protagonists' own voices, it's a look into the heightened tension in the air.

Enter Harry Edwards from San Jose State University, a vocal activist who realized the potential that athletes, and Olympians in light of the approaching Games, could be instrumental in promoting activism. The resultant Olympic Project for Human Rights pushed for a blanket boycott by Black athletes at the Games, supported as a strong symbol of "protest and struggle against racism and injustice", and was seen as the first time a group of athletes took a stand together. Eventually, the boycott movement fizzled but individual athletes were encouraged to contemplate individual actions - perhaps refusing to take a place on the podium?

With that backdrop, Smith and Carlos enter the Games and medal in the 200 meters (Smith gold, Carlos bronze). We know the moment on the victory stand: wearing beads (Carlos) and a scarf (Smith), and walking shoeless, they shared a single pair of black gloves, they bowed their heads, and led by Smith - and fatefully - raised a fist both during the national anthem and on the walk back from the podium. But hearing directly in retrospect from the two, we gain insight into the spontaneity of the fists gesture. Interestingly, Smith posits the raised it as a sign of "solidarity and strength" rather than specific alignment to the "Black Power Movement" - a label very hard to disassociate since.

The immediate aftermath is well-known: led by IOC president Avery Brundage's indignation, Smith and Carlos are thrown out from the Olympic Village and banned by the U.S. Olympic Committee. What a juxtaposition to the USOC's stance now....with recent Black Lives Matter activisim as inspiration, today's USOC has expressed direct support for athletes who may protest. Just as surreal, World Athletics commemorates the moment as "iconic".

A memorial to the moment lives at San Jose State

A memorial to the moment lives at San Jose State An unexpected strength of the film is the recounting, complemented by great archival footage, of the fateful 200 meters race itself. Smith's world record victory came after a pulled muscle in the semifinal just hours earlier, setting extra drama into the final.

The Stand indicates a direct line to current activism, including Colin Kaepernick's kneeling, which could have been enhanced with comments from later athlete activists and their perspectives on 1968 to provide a fuller circle back. In fact, the next Olympics at Munich 1972 had its own podium protest, an obvious direct result of Mexico City. But in all, The Stand offers a sympathetic look back at the protest and at what Smith describes as a "responsibility to stand up for humanity".

Rower Livingston contemplates in admiration that Smith's and Carlos' protest was a "piece of performance art". It's also an indelible moment in Olympic history that reverberates today, as the discussion on podium activism continues, no matter how the IOC attempts to brush it aside.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed